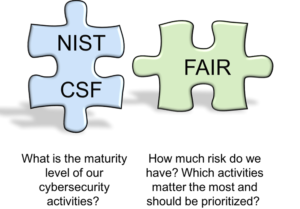

The question often arises, “How is FAIR different from (or better than) a framework like NIST’s Cybersecurity Framework (CSF)?” The simple answer is: FAIR isn’t inherently better or worse; it is fundamentally different and, in fact, complementary.

The question often arises, “How is FAIR different from (or better than) a framework like NIST’s Cybersecurity Framework (CSF)?” The simple answer is: FAIR isn’t inherently better or worse; it is fundamentally different and, in fact, complementary.

Frameworks as lists of good practices

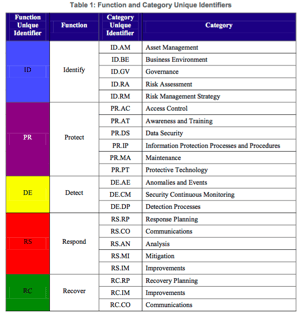

Frameworks like the NIST CSF (or PCI DSS, ISO 2700x, COBIT, etc.) are essentially lists of good practices.

"The Framework enables organizations – regardless of size, degree of cybersecurity risk, or cybersecurity sophistication – to apply the principles and best practices of risk management to improving the security and resilience of critical infrastructure." (Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity. NIST)

In other words, by reliably complying with the elements in those frameworks, an organization is implicitly assumed to have less risk than if it didn’t. Although this is logical and has its uses, it doesn’t address this important pragmatic fact: organizations will always have gaps in their compliance with such frameworks, especially over time, and they will need to prioritize these gaps based on risk.

In other words, by reliably complying with the elements in those frameworks, an organization is implicitly assumed to have less risk than if it didn’t. Although this is logical and has its uses, it doesn’t address this important pragmatic fact: organizations will always have gaps in their compliance with such frameworks, especially over time, and they will need to prioritize these gaps based on risk.

These frameworks also tend to set a lowest common denominator bar, meaning compliance doesn’t necessarily equate to “sufficient” risk management practices. The problem is, because checklist frameworks don’t assist in actually measuring risk, organizations are left to their own devices to evaluate whether compliance is sufficient. This is where FAIR comes in.

FAIR: an analytic model

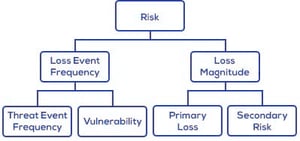

FAIR is an analytic model that enables an organization to evaluate and measure the significance of gaps or the sufficiency of compliance so that it can make well-informed choices about where to apply its limited resources.

Because FAIR enables true quantitative measurement in economic terms (versus more common ordinal measurements), its results are inherently meaningful to business executives. As a result, FAIR is complementary to good practice frameworks and fills an important gap from which all such frameworks suffer.

Because FAIR enables true quantitative measurement in economic terms (versus more common ordinal measurements), its results are inherently meaningful to business executives. As a result, FAIR is complementary to good practice frameworks and fills an important gap from which all such frameworks suffer.

Digging deeper

Over the next several weeks, I’ll publish a series of blog posts that will seek to do several things:

- Outline the positive aspects of NIST CSF, as well as areas where if falls short and where improvements are needed. This is intended to help readers understand its strengths and limitations so they can:

- Use the CSF appropriately and not try to gain utility from it that it simply cannot provide in its current state

- Encourage NIST to evolve the CSF and reduce its limitations

- Better understand how to use FAIR to complement the CSF

- Describe and give examples of how FAIR can be used to draw additional value out of the CSF

Hopefully, although primarily focused on the CSF and FAIR, these posts will also provide a useful lens to view the broader landscape of risk management and information security frameworks and methods.

Stay tuned for Part 2.